Finance Canada: No More Spring Budgets

Evelyn Jacks

Finance Canada announced on October 7 that Canada’s federal budgets will be brought down in the fall starting with the November 4, 2025 event; a significant departure from the spring schedule (February, March or April) that has been the cycle for several decades. This is going to affect many other events as we know them, and in the annual government spending approval cycle. There will also be a new budget process for capital vs. operational expenses. Here’s what you need to know:

Why a Fall Budget Cycle? Finance Canada notes that tabling a budget a few months before the start of its fiscal year (April 1) aligns with OECD best-budget practices.

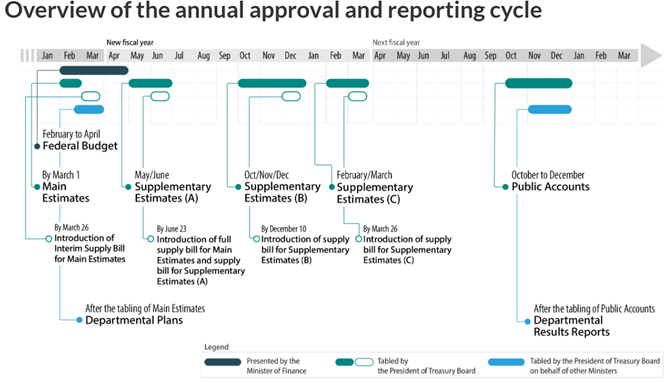

It also points to greater predictability and better planning opportunities across interested sectors: businesses, investors, organizations, provincial and territorial governments. In addition, more budget measures can be included in time for the Main Estimates, so that elected parliamentarian can better oversee the public expenditures. These must be tabled by March 1 every year. The existing process, shown below, will need to be overhauled:

A fall budget also better aligns with construction seasons, important as the government implements its Build Canada Homes strategy. Now, fall budget spending announcements can get Parliamentary approval well before construction season.

This change in the budgeting cycle will also change two other important interactions:

- The Pre-budget consultations, which will now take place in summer.

- The Budget will be the government’s main annual fiscal event, followed by a spring economic and fiscal update as the new fiscal year begins on April 1, as opposed to the old cadence which saw a Fall Economic Statement in October, November or December.

The New Capital Budgeting Framework. According to Finance Canada, this new methodology will establish a consistent way to classify spending that contributes to “capital formation”, including tax expenditures. The government refers to those expenditures as capital investment.

What is Capital Investment? This is defined broadly as follows:

“. . .any government expense or tax expenditure that contributes to public or private sector capital formation, held directly on the government’s balance sheet or on that of a private sector entity, Indigenous community or another level of government.”

According to Finance Canada, capital investments will include:

- Measures to grow the housing stock - measures that accelerate new housing supply.

- Capital transfers - transfers to other levels of government and organizations expressly intended for the recipient to invest in infrastructure or a productive asset.

- Capital-focused corporate income tax incentives - tax expenditures intended to incentivize new capital formation.

- Amortization of federal capital - expenses recorded to spread the cost of capital assets owned or controlled by the federal government over their useful lives.

- Private sector research and development - direct funding, or tax incentives, for research and development activities that enable commercialization or scale-up and raise future productive capacity.

- Support to unlock large-scale private sector capital investment - contractual agreements with proponents involving exceptional, significant operating subsidies designed to unlock incremental large-scale private capital investments.

Why This Change, Now? The intent is to focus on capital investments that meet the following criteria:

- Conditionality – whether the funding recipient is required to invest in capital formation to receive the benefit.

- Clear linkage – whether the spending encourages or enables capital investment in identifiable sectors or projects.”

What is Operational Spending? This is defined as “spending that is not categorised as capital investment . . .(including) major government expenditures like transfers to persons, health and social transfers, and the costs of running government operations and services, including salaries and benefits.”

Why these Changes Make Sense. The federal government wants to catalyze a renewed commitment from both the public and private sectors to make capital investments a national priority. It says that Canada has fallen behind other countries which have made accelerated investments in intellectual property, advanced technologies, and modern manufacturing to strengthen their economic potential.

Kevin Page, President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, senior fellow at Massey College, and a former Parliamentary Budget Officer, also notes other nuances in his October 6 article in Policy Magazine:

“Not all debt is the same. Young Canadians and future generations will mind less if they pay debt-interest charges on assets they can use and see versus the consumption of spending long gone.”

That remains to be seen. The fact is, that spending long gone, and continuing, has ballooned the spend on interest payments and contributed to our unprecedented federal debt and deficits. The Fraser Institute, in its publication Federal and Provincial Debt Interest Costs for Canadians, 2025 edition, notes that taxpayers across Canada will pay a total of $92.5 billion on interest payments for the federal and provincial government debts in 2024/25 alone.

In fact, this report notes:

“The federal government will spend a projected $53.8 billion on debt servicing charges in 2024/25, which is more than what the government expects to spend on the Canada Health Transfer ($52.1 billion), and significantly more than it expects to spend on childcare benefits ($35.1 billion).”

. . . Further, “residents in Newfoundland & Labrador face the highest combined federal-provincial interest payments per person ($3,432). Manitoba is the next highest at $2,868 per person.”

The Bottom Line: High government debt – capital or operating – increases interest costs that erode spending room for social benefits and other priorities and pass costs along to future taxpayers.

But according to the IMF,(International Monetary Fund), no matter how you slice it, high debt brings with it critical challenges for governments: reduced capacity to provide support for ailing banks, which could culminate in a more vulnerable financial sector, is one of them. Another: the possibility that countries which are borrowers could face “a new normal with significantly higher funding costs than in the past decade.” Against what it calls dimming prospects for economic growth, elevated real long-term interest rates could pose significant challenges.

Those are some of the metrics future taxpayers will want to bear in mind as the Federal Government unveils its November 4 budget and new accounting policies.